Students want to “have a degree” and “get a good grade” rather than be learners and it then becomes logical for them to ask questions such as “will this be in the test?”, in order to avoid wasting effort on unrewarded content (for more on the whole having vs being debate I highly recommend Fromm’s “To Have or to Be”). This attitude is precisely the opposite of what we should be encouraging if we want to produce a society of self-motivated and reflective lifelong learners. To make matters worse, although renaming classes as “guilds”, grades as “levels” and better marks as “leveling up” may manipulate learners into modifying their behaviour, it does so by reinforcing and perpetuating an anachronistic industrial model of education through concealment and thwarting intrinsic motivation. Prepackaged web 2.0 services like Class Dojo promise to enable teachers to:

"Create an engaging classroom in minutes” by providing “instant visual notifications for your students (‘Well done Josh! +1 for teamwork!’) with a whole host of game mechanics: think level-ups, badges and achievements to unlock, in-classroom games, avatars and leaderboards.

Similar gamification platforms are popping up every day, their brightly coloured, cutesy vector graphics thinly concealing the underlying rhetoric of increasing reward dependency and undermining intrinsic motivation.

Dewey expresses this nicely in chapter seven of The School and Society:

If there is not an inherent attracting power in the material, then (according to his temperament and training, and the precedents and expectations of the school) the teacher will either attempt to surround the material with foreign attractiveness, making a bid or offering a bribe for attention by "making the lesson interesting"; or else will resort to counterirritants (low marks, threats of non-promotion, staying after school, personal disapprobation, expressed in a great variety of ways, naggings, continuous calling upon the child to "pay attention," etc.); or, probably, will use some of both means.

...But the attention thus gained is never more than partial, or divided; and it always remains dependent upon something external —hence, when the attraction ceases or the pressure lets up, there is little or no gain in inner or intellectual control.

Such instrumental learning may be easy to implement and convenient for administrators to tidily quantify into grades and statistics, but we need real change in education, not merely a shift in perceptions. Games can help us achieve this if we respect and embrace their complexity and refrain from stripping them of their intrinsic power to motivate and engage learners on multiple levels. Educators can and should use games and game mechanics in different contexts, but they should do so reflectively and unravel their underlying rhetoric. Games can serve as excellent examples of how active and stimulating learning environments can be created for the purpose of learning, as good games already embody many of the characteristics of good learning principles (see James Gee for more on this and John Hunter’s World Peace Game for a real-world example of a gamified learning program that embraces the rich complexity of game dynamics).

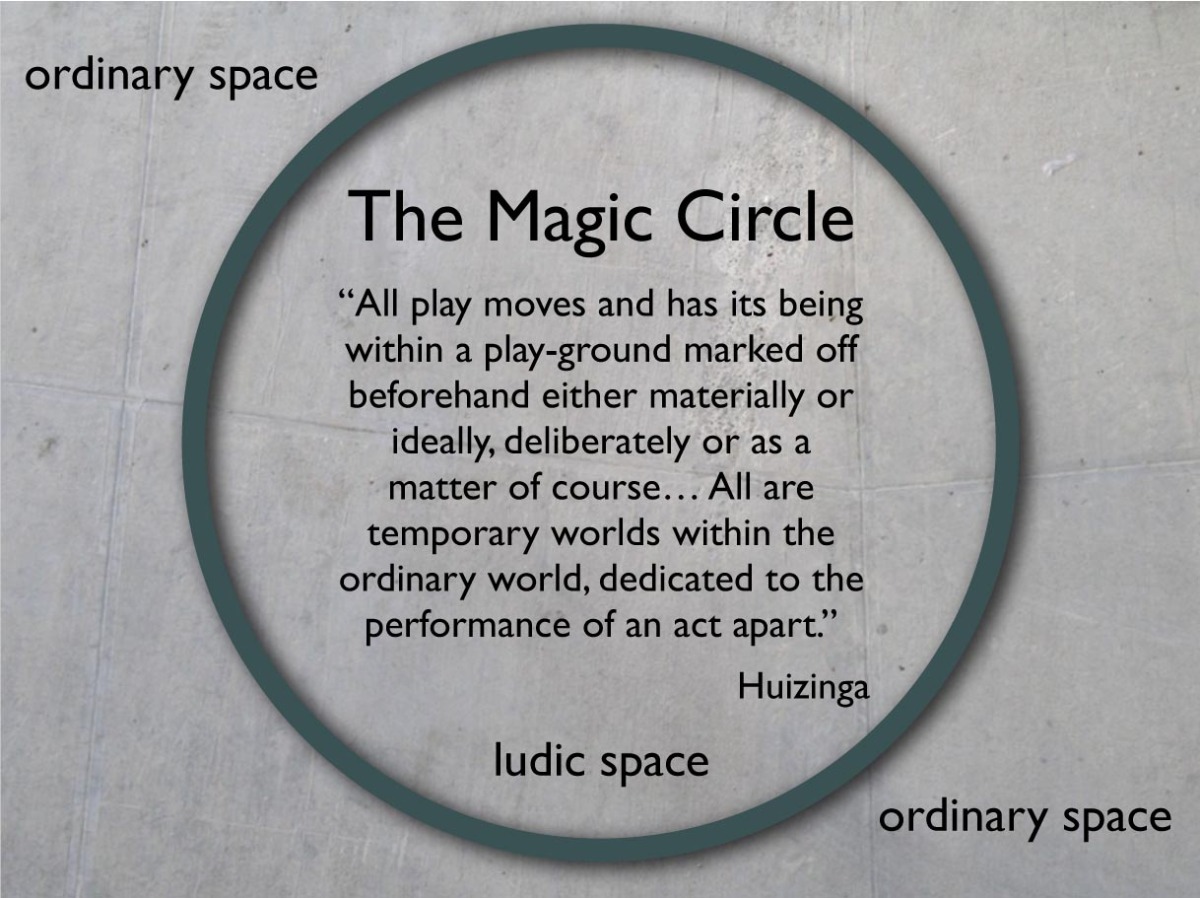

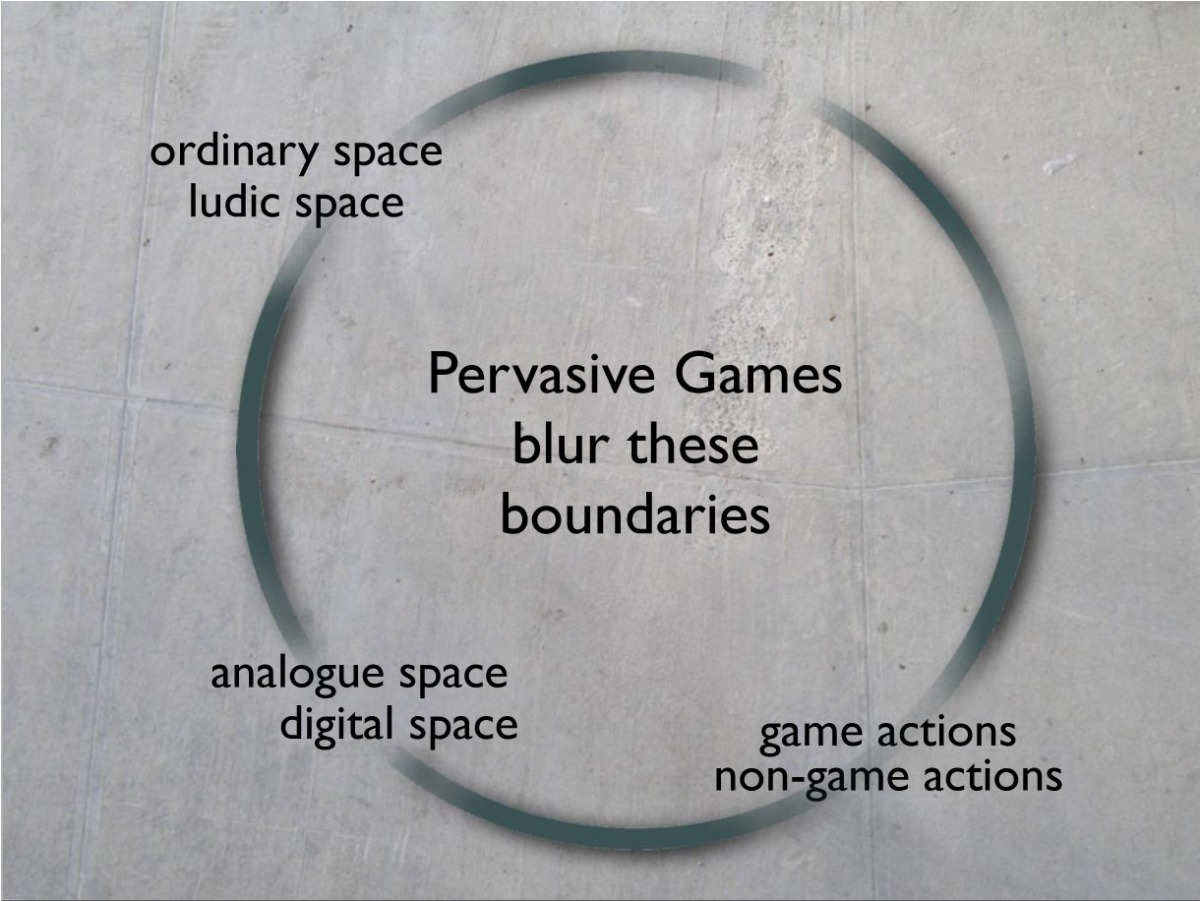

So the problem of gamification is, somewhat ironically, that in the majority of its current implementations, it is not game-like enough. By overlooking the depth and breadth of the potential games have to empower and motivate learners and create meaningful experiences, and instead employing only a myopic and superficial game mechanic, popular gamification is doing a disservice to both learners and educators. Completing tasks in order to achieve an extrinsic reward is more akin to how we describe work in its most alienating form. One of the many things commonly missing from gamification is playful freedom. Playful freedom allows learners to take risks and test new strategies in an environment protected within the “magic circle” of gameplay, that is safe from real world consequences. An environment in which failing at challenging tasks is as integral a part of learning as succeeding, and the reward is the learning that takes place between the two, and what that skill or knowledge might empower you to do or be in the future.